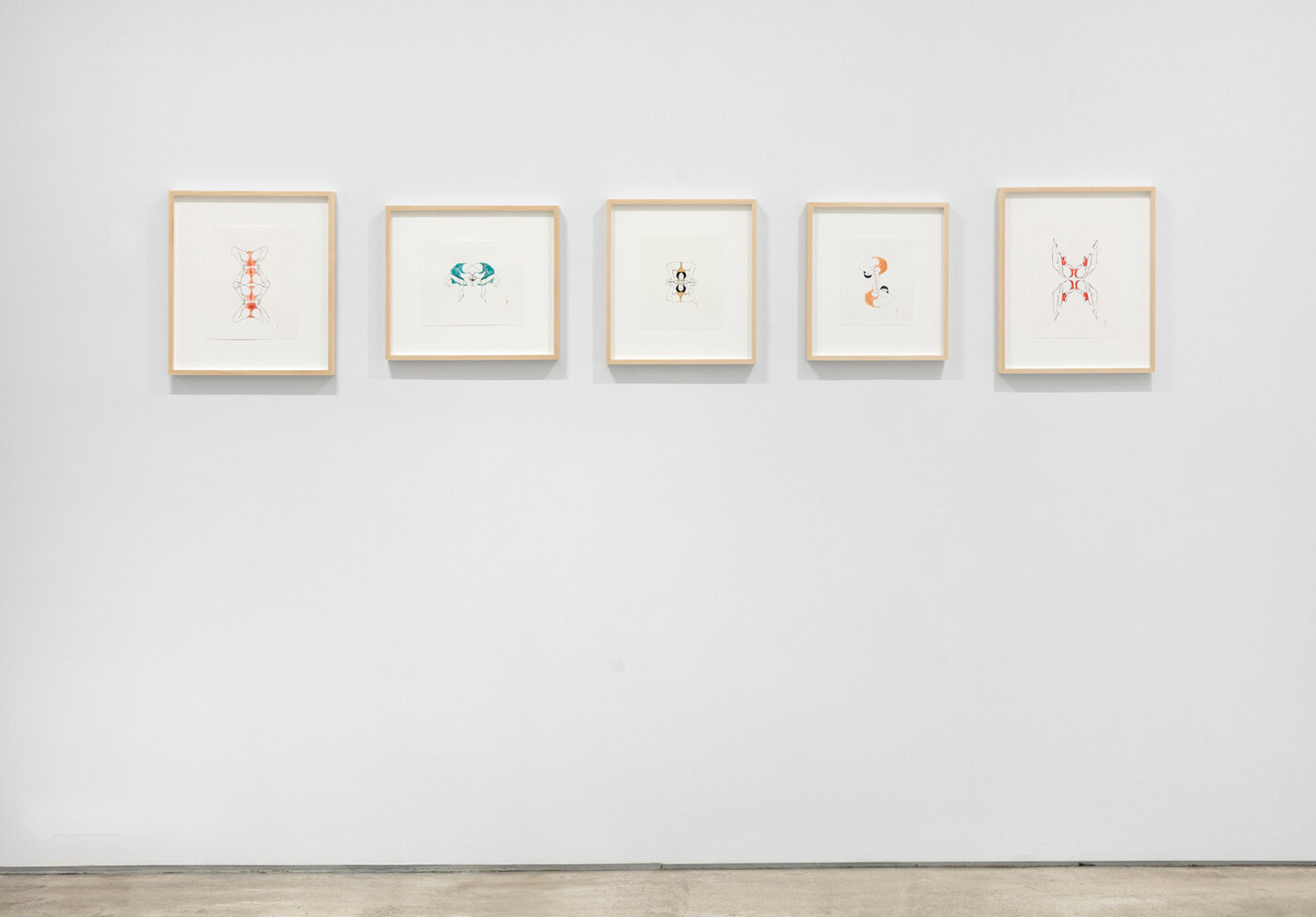

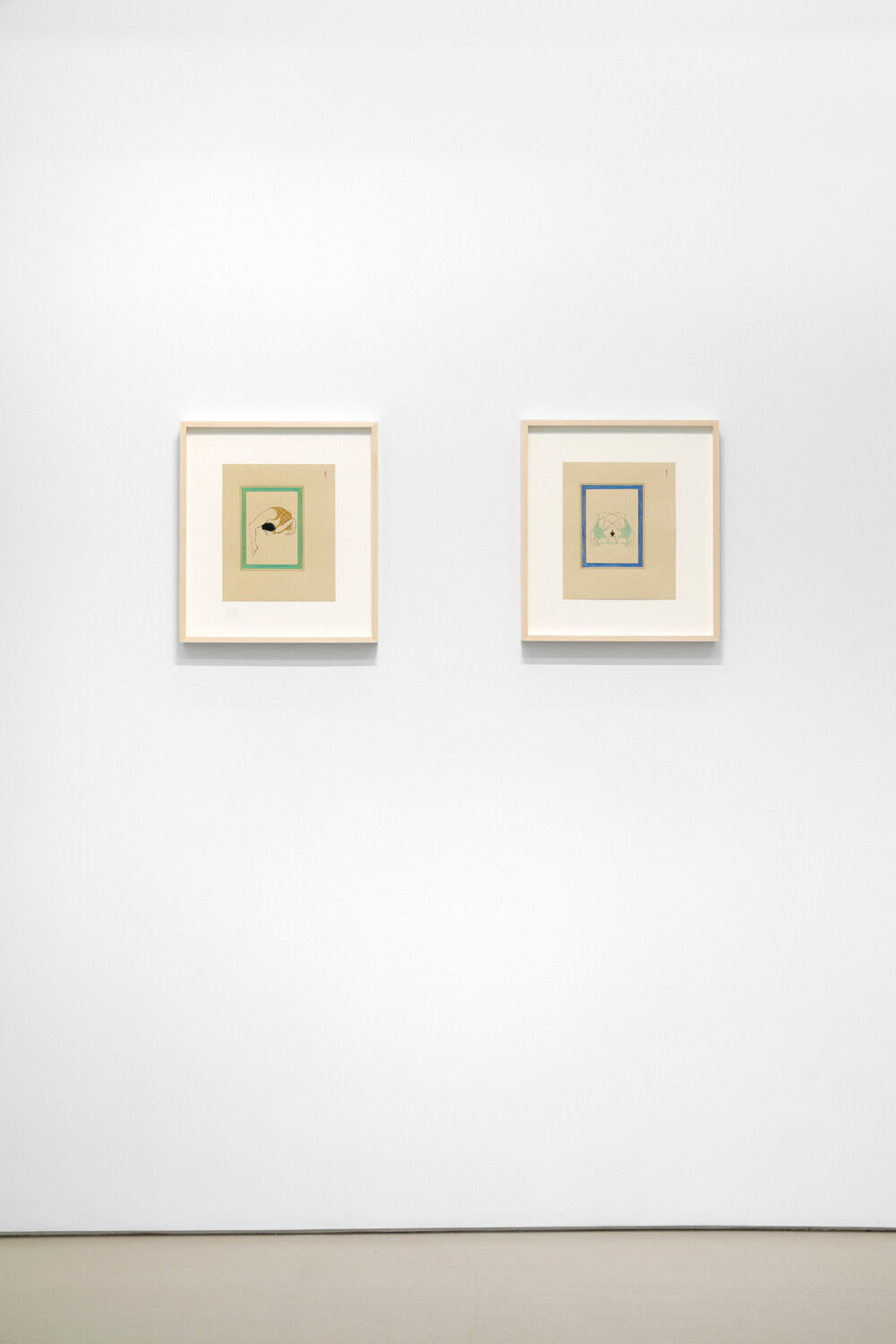

Hayv Kahraman: Not Quite Human

Works (Tap to zoom)

Press Release

Hayv Kahraman

Not Quite Human

September 5 – October 26, 2019

524 W 24th Street and 513 W 20th Street, New York, NY

Jack Shainman Gallery is pleased to present Not Quite Human, a new body of work by Hayv Kahraman and the artist’s fourth solo exhibition at the gallery.

The following is an excerpt from the essay, “Bending and torqueing into a ‘willful subject’”, written for this exhibition by Madina Tlostanova, Professor of Postcolonial Feminisms at Linköping University, Sweden and the author of Postcolonialism and Postsocialism in Fiction and Art: Resistance and Re-existence.

In her new project, Hayv Kahraman documents a process of transformation of an obedient object into a mischievous “willful subject”[1]. The space of this metamorphosis is the body that ceases to be a silent emblem of its own suffering, to become a site of agency and empowerment, a decolonial “killjoy” who breaks out of the system of paralyzing oppositions that still define our lives: man/woman, white/colored, human/natural, home/exile. […]

All of her works are ultimately reflections on otherness and othering as a form of dehumanization, focusing on the gap between the immigrant, non-white, genderly marked other and the way she is perceived by the white hetero-patriarchal normative same. The art of contortion,[2] selected as the main metaphor of this series, is a liminal space per se. In its euromodern commodified form it belongs to the forbidden realm of freak shows with their typical temporary cancellation of decency prescriptions for the white male subject. The audience of the freak show does not identify itself with the freak, but on the contrary, rejoices in its own normality even if it is thrilled with a temporary seduction into/by the abnormal, the sexualized taboo. Ann McClintock described this effect as “involving the fetishistic principle of collection and display and the figure of panoramic time as commodity spectacle”[3]. Stretching the boundaries of normativity, it accentuates such forms of othering as exoticization, fetishization and dehumanizing eroticism[4].

One of the main conceptual and affective elements of this series is its ambivalence, the interplay of the opposite meanings within one image. Such are the haunting bodily pyramids interweaving the elements of identical bodies and differently-expressioned faces, gathering into monstrous multiple selves. The bodies are positioned in a sexually provocative and extremely submissive and humiliating way yet at the same time, are decidedly powerful and threatening[5], triggering the mixture of the desire and fear of the other[6]. […]

Above all, this series documents the metamorphoses of a trickster in its rather rare feminine form. Trickery as a traditional weapon of the weak becomes empowering, turning the trickster into a willful subject who feels at home in an alluring and threatening liminal space. Kahraman’s tricksters are boundary crossers and border dwellers. They are disrupting the rigid dichotomy of obedient assimilation and open revolt, through living out an alternative of ambiguous subversion, exotic-erotic seduction, manipulating and mocking, utilizing the distorted “master’s tools”[7] to their benefit, eventually causing the power to crumble.

One of the main trickster’s tricks is disguise which can at times come to a shape-changing. In Kahraman’s contortionists, this mutability is embodied literally as the trickster’s modus vivendi and a way of survival and re-existence. Yet as in all Kahraman’s works there is an additional hidden motif linking tricksterism to her traumatic experience of the war in Iraq, to its disfigured and dismembered mine victims, so that bricolage becomes an almost literal and physical magic act of stitching one’s body together from many discarded and mismatched parts. The trace of this painful local history is ever present in the agonizing facial expressions and distorted postures of contortionists. It is the artist’s way of exposing the colonial wound[8] and attempting to heal it, however impossible this task may be, through the punishing and avenging incarnation of the trickster.

The dynamics of Kahraman’s technique also reflects different stages of metamorphosis. It is expressed in the gradual shift from more “realistic” Renaissance-style depictions to increasingly non-representational and even abstract ones. This effect is reached through the use of blurred and half-transparent vanishing figures with eroded boundaries. Depicting different stages of transformation with the help of the increased transparency and blurriness, the use of toning, hazing, gradation, sfumato, Kahraman goes further and further away from the canonical euromodern depiction of the normative white body, and more and more confidently shaping her own language delinked from the master’s tools. […]

Problem people are mostly balancing on the verge of physical survival and losing control over anything including their bodies as the last refuges of resistance. When people have no control over anything, the last space of confrontation is the body[9]. Yet it is also the first trigger of liberation, transgression and re-existence as any awareness starts with the body as the first instrument we are given to make sense of the world. The non-white body is systematically represented as abnormal, a subject of secret self-abhorrence in need of “white-washing”. Through its rehabilitation and symbolic empowerment, Kahraman attempts a decolonial catharsis. This non-normative body is as ambivalent as Dubois’s “double consciousness”[10]. It incorporates the pain and its overcoming, the submission and resistance to it, the humiliation and reinstating of one’s dignity. In the end, the bodies of Kahraman’s contortionists serve as powerful material mediators of resistance and re-existence, empowering independent actors who could rephrase the Fanonian prayer: “O my body, make of me always a man who questions!”[11] into “O my body, help me question the mastery that is leaving us no chances, and create myself and the world anew!”

Hayv Kahraman was born in Baghdad, Iraq and lives and works in Los Angeles. Her work is currently on view in Suffering from Realness, at MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA, through January 1, 2020. Forthcoming exhibitions include Modest Fashion, Stedelijk Museum Schiedam, Netherlands; How the Light Gets In, Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY; In Plain Sight, Henry Art Gallery, Seattle, WA; New Time: Art and Feminisms in the 21st Century, BAMPFA, Berkeley, CA; and When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art, ICA Boston, Boston, MA, which will travel to the Minneapolis Institute of Art and the Cantor Arts Center in Stanford. She has had recent solo exhibitions at the Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture & Design, Honolulu, HI; Honolulu Museum of Art, HI; De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill, UK; Pomona College Museum of Art, Claremont, CA; Contemporary Art Museum, St. Louis, MO; and the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, NE. Her work is included in several public collections such as Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, North Carolina Museum of Art, The Rubell Family Collection, The British Museum in London, The Barjeel Art Foundation in Sharjah, and MATHAF Museum of Modern Art in Doha.